About the Women's Alliance

All Souls Women in the Nineteenth Century

The Women’s Alliance was formed in 1890, but the women of All Souls were always a very active part of the congregation alongside the men, coming as they did from liberal, free-thinking backgrounds. The first members represented a wide range of religions and cultures, but they were all drawn by the idea of a tolerant, liberal religion. As Catharine Sedgwick, a novelist and member of the church, wrote to her friend, Eliza Lee Cabot, there were "strangers here from inland and outland, English radicals and daughters of Erin, Germans and Hollanders, philosophic gentiles and unbelieving Jews.”

All Souls was founded in 1819 as a liberal Congregationalist church. Lucy Channing Russel, the sister

of Rev. William Ellery Channing, a famous Unitarian Congregationalist minister in Boston, had invited him to

give a talk on his unitarian views at her house in lower Manhattan to about forty of her friends. Rev.

Channing’s talk argued that the doctrine of the Trinity subverted the unity of God, that Jesus was fully

human rather than divine, and called for the Bible to be interpreted through reason.

Channing’s message struck a chord and inspired the attendees to found the church which they initially

called the First Congregational Church of New York. At first they met in a townhouse at Broadway and

Reade Street, but changed the church’s name and location several times in the decades ahead. They adopted

the name "The Unitarian Church of All Souls" in 1855. (For more information, see the All Souls Historical Society website.)

In the 1820s, the women of All Souls began a tradition of charitable work by starting a free school for the poor in the church basement. “Our plan is to have it kept in one of the lower rooms of the church, kept by a woman and superintended by the ladies,” Catharine Sedgwick wrote in 1823. “We mean to teach the children the rudiments of learning, how to mend and make their clothes and darn their stockings. Our society is small, and far from rich, but we hope to accomplish it.”

Many of the local Protestant and Catholic churches also taught poor children and provided clothing for free, but they did not embrace families of different religious persuasions as this church's school did. In 1826, an article in the Christian Inquirer reported that during the previous year, 94 children had been educated at the school, with the cost borne entirely by the women of the congregation. The school continued for nearly two decades.

As the Civil War began in 1862, women everywhere began organizing to discuss what they could do to support the Union troops. A few days after the war began, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, a Unitarian and the nation’s first female physician, invited some of the most prominent ladies of New York society to a meeting to form an aid association. Among them were members of All Souls like Sarah Bedell Cooper (Peter Cooper’s wife), Frances Bryant (William Cullen Bryant’s wife) and Louisa Lee Schuyler. The minister of All Souls, Rev. Henry Whitney Bellows, was one of the few men invited. Dr. Blackwell was particularly concerned about the sanitary conditions on Staten Island, where hundreds of military volunteers had pitched tents on their way to Washington D.C.

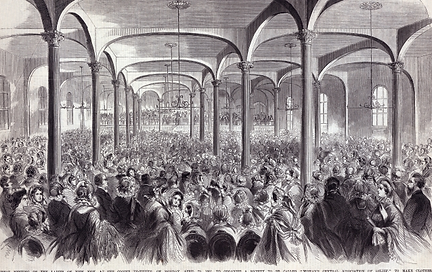

Word spread rapidly about the effort, and the following week more than 4,000 women gathered at Cooper Union and formed the Women’s Central Association of Relief. Its aim was to organize a volunteer network that would collect food, clothing and medical supplies for Union soldiers and train nurses to work in military hospitals. They asked Rev. Bellows to serve as their president. The Women’s Central, as it was called, rallied women across the country in the following months. Besides making uniforms and collecting donations, women volunteered to cook, serve and run kitchens in army camps, manage hospital ships and operate lodges for traveling and wounded soldiers. The organization was a vital force throughout the Civil War, supporting the U. S. Sanitary Commission set up and chaired by Rev. Bellows, and ultimately contributing goods and services valued at over $1 billion to support the troops.

In the process, the Women’s Central also provided its female managers with rare opportunities to operate outside traditional expectations for women as they traveled the country and negotiated with civic organizations and businesses. Although she was just 24 years old, Louisa Lee Schuyler served as the group’s corresponding secretary and ran its office in New York.

Lucy Channing Russel

Meeting to form the Women’s Central Association of Relief, 1862

All Souls' first building on Reade Street,

when it was still called First Congregationalist

Formation of the Women’s Alliance

Unitarian women had been organizing church affairs, raising money and doing good works ever since their churches were established. In the 1870s, buoyed by their work in the Civil War, women began organizing on the denominational level to marshal their forces and strengthen their collective voice.

At a large meeting of the National Conference of Unitarian Churches in Saratoga, New York, in 1878, a group of participants founded the Women’s Auxiliary Conference, with the aim of stimulating and raising money for local charitable and missionary work. By 1890, the women’s group had 80 branches, and a membership of nearly 4,000 women, but it was still an auxiliary to the National Conference of Unitarian Churches.

The New York League of Unitarian Women, started by Velma Wright Williams of All Souls, had

shown the advantages of a separate and closer organization, and a committee was formed

to draft a constitution for a new organization. In 1890, the Women's Auxillary was reborn as

the National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Liberal Christian Women, aiming “to quicken

the life of our Unitarian churches, and to bring the women of the denomination into closer

acquaintance, co-operation and fellowship.” Velma Williams drafted the organization’s

constitution from her home. The All Souls branch of the National Alliance was formed in 1890.

All Souls' 3rd building, on Park Ave. and 20th St.

The Women’s Alliance in the Twentieth Century

For nearly 140 years, the Women's Alliance has been one of All Souls' most active organizations. When it was founded, its objectives concerned the religious life of its members and missionary and benevolent work. Meetings, often including lectures by clergy or well-known authors, were held monthly except during the summer. A basket was passed for donations to support the work of the group.

One of the longest running programs was the Cheerful Letter Writing Committee, founded in 1915 to write letters and send gifts to shut-ins and people without family support. The committee continued for decades and later sent packages of supplies to rural schools and needy families. The letter-writing was curtailed in 1960 due to lack of space in the church, but the committee continued to provide toys and make bandages for hospital wards.

Other Alliance activities included greeting visitors to the church, serving coffee on Sunday mornings, hosting lectures and organizing the annual All Souls Fair. The first mention of the fair in the Women's Alliance records was in 1924, when it held a $1.00 white elephant sale (featuring unusual or useless items) as well as books, jams and baked goods. The Alliance managed the fair, which became one of the church's major fundraisers, until the 1970s.

Women of the congregation started working months in advance, knitting, sewing, pickling and making jams and jellies to sell. Volunteers solicited donations of toys, games, plants, jewelry, housewares, antiques and vintage clothing. “During the Depression, handmade items became an important aspect of the fair,” Maxine Beshers wrote in a 2008 article in the Quarterly Review. “Wealthy members of the congregation would retain the servants of their summer homes to make gifts, rather than dismissing them, in those critical times.”

By the time Anniversary Weekend rolled around in November, Fellowship Hall was filled with sales tables

overflowing with handmade hats, mittens, baby clothes, breads, cakes ,cookies and curiosities of all kinds. People

of all ages participated: children ran the coat room, teenagers helped served a seated dinner. The festivities

usually began on Friday evening with a preview just for church members. On Saturday, the fair was open to

the public and people came from far and wide. The antique table often attracted dealers. Families came for a

festive lunch and could take a home a boxed dinner. There was entertainment all day long, including games,

sing-alongs, skits written and acted by church groups and musical performances by those professional and not.

Over the years, the fairs became ever more elaborate and expansive. One year, the Minot Simons room was

piled high with more than 4,000 donated books. Upstairs, the vestibule became a popular flea market. Local

merchants and restaurants were encouraged to take out ads in a professionally-produced program and donate

to the sales tables. One year a single volunteer, Rosa Bellamy, brought in contributions from over 100 neighborhood businesses.

As the fair’s organizers, the Women’s Alliance determined how the proceeds should be divvied up among the causes they supported, but this changed a little in 1975, when church finances were at a low point. The All Souls Board of Trustees became a co-sponsor of the Annual Fair and a board-appointed committee divided the revenues. Income from the fair was a line item in the church budget for several years. From the mid-80s on, the proceeds were used exclusively to support the church's burgeoning outreach programs, including the Booker T Washington Learning Center, the Adopt-a-School Program, and the Monday and Friday meal programs. The biggest money-maker of the fair was the live auction, which became renowned for its travel bargains. Volunteers solicited donations of surplus hotel rooms around the world, airline tickets and cruises, and packaged them together into exotic trips. Winning bidders could venture to Africa, China, Russia and the Caribbean, for far less than they would normally pay, and all for good causes.

In 1982, the Alliance learned of the Clara Barton Sisterhood, which honors Unitarian Universalist women who are at least 80 years of age who have served their churches and communities for many years. Martha Bartlett, who had served as president of the Alliance and recently died, was the first member from All Souls. After a hiatus, the Alliance resumed nominating two or three members a year in the early 2000s. Peggy Montgomery and Maureen Marwick were inducted into the Sisterhood in 2018.

Georgina Schuyler, Women's Alliance member and the first woman elected to the Board of Trustees of All Souls at the age of 83 in 1923. She was the sister of Louisa Lee Schuyler, and they were great-granddaughters of Alexander Hamilton.

A 1970s flyer for the Fair

The Twenty-First Century

In 2001, the Alliance established an endowed fund to honor long-time member Angie Utt with an annual lecture series focusing on women and American culture. Lecturers have included film director Nancy Savocca, New York City Councilwoman Eva Moskowitz, US Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, and actor Jessica Hecht.

The Women's Alliance, which has been a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization since 1960, has been sustained in part by generous donations and bequests. Earnings from its investment account, along with dues, gift table sales and other donations, help support its program and charitable giving.

Today, the Women's Alliance remains one of the oldest and most active organizations at All Souls. Its programs include regular Wednesday luncheons with speakers, seasonal social events and outings to places of interest. Special Interest Groups meet regularly. Currently, these include the Women's Reading Group, the Safety Group, which discusses issues of personal and public safety, and a group that gets together to attend free and inexpensive concerts.

Preparing for the Holiday Sale

Birding in

Central Park

An outing to the Dia Chelsea

Preparing for the Holiday Party